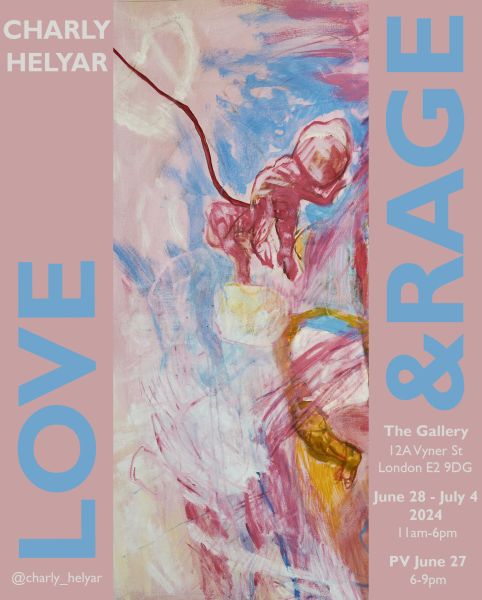

At the heart of Charly Helyar’s work lies a deep, raw humanity charged with love, rage, vulnerability and tenderness. Whilst she employs expressive abstract mark-making, the figure is always central to Charly’s work, allowing her to convey the complex emotions and sensations that make up the essence of our shared human condition. Alongside her art practice, Charly has been a paramedic for the last 20 years and thus exposed to the complete vulnerability of strangers, both physically and emotionally, on a regular basis. With this first-hand experience of seeing bodies in every possible state, Charly has developed a mastery of representing the body.

In the recent body of work exhibited in LOVE & RAGE, Charly uses this ability to express her emotions. Faced with devastating global news in the media, she is outraged by the onslaught of violence, prejudice and bigotry that we witness on a daily basis. In her paintings, the figure of the dead baby stands as a symbol of all innocent, vulnerable people - the very act of killing them breaches our sense of basic human decency, displaying a total lack of mercy and compassion. These injustices spark an indignance borne out of love and care, as opposed to the anger felt by others, which is fueled by a thirst for destruction and domination. Yet, concurrently, Charly finds solace in her personal experiences of love, family, friendship and romance, manifested in a warm embrace, a kiss, a smile. In her paintings, she proposes that love and hope have the power to overcome violence and despair.

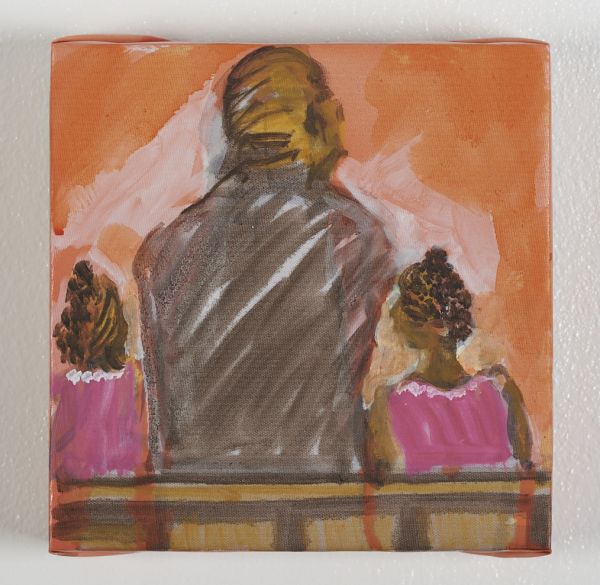

Charly has the ability to hold extremes within a single image and to blur the sometimes fine line between them. A figure may be contorted by the pain of convulsions or the ecstasy of sex, an electrical current running through the body. A hand with stretched bony fingers can be at once threatening and seductive. Charly uses alluring candy colours to tackle difficult subjects, and combines bold, energetic lines with slow, detailed marks. And scale plays its part too. One might assume that the large works are about rage and the small works are about intimacy. This is a generally accepted principle in art history: large is male, active, strong, historic, whilst small is female, intimate, domestic, passive. But once again, Charly blurs these lines by proposing that the small domestic moments can be just as large and important as a historical scene. Equally, as viewers, when we’re able to find individual human figures amongst the chaos of devastating events, we regain the ability to care.

Eloise is a multi-disciplinary visual artist and curator. After a joint Fine Art & History of Art degree at Goldsmiths, she graduated from an MA in Fine Art at City & Guilds of London Art School in 2023.

IN CONVERSATION:

CHARLY HELYAR & GEMMA CORNETTI

Gemma Cornetti: I know you draw all the time and define yourself as ‘a drawingy painter rather than a painty painter’ and that there’s an ongoing dialogue with artists from the 16th century. In Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1568), Giorgo Vasari wrote that the disegno was ‘the father of our three arts: architecture, sculpture, and painting’. Can you tell us more about how you conceptualise drawing and how it works as the foundation of your practice?

Charly Helyar: Drawing is the most important thing for me. If I don’t draw for a bit I get quite agitated, it picks me up and soothes me. It’s the structure that underpins my practice and it fulfills so many needs. I use it to get down quick visual notes from life, for example when walking along. I can then reconstitute a more detailed drawing from them by fixing the basic image in my mind. I do lots of compositional drawings, the same thing over and over, trialing subtle changes. I also do very detailed slow drawings, sometimes these can take ages. I’m interested in how the most imperceptible mark can make a difference to the final image. My preferred mediums at the moment are pen and ink, wax resist, watercolour and wax crayon, whilst charcoal powder is an old friend. If I’m in a painting phase, this tends to feed back into the drawing, and vice versa. It’s good for my confidence – if I’ve worked on something in drawing I’m confident I can achieve what I want in painting.

GC: Let’s discuss the polarity of figuration and abstraction in your works. You are attracted to the human body, yet the figures in your paintings are hardly recognisable. Have you always leaned more towards one rather than the other? Why this choice?

CH: I’ve always had this dual interest in my work, but I felt before it was ‘either, or’. I find highly figurative work dull; there’s no room for my imagination, nowhere for me to go and make my own story. On the other hand, I have also made completely abstract work which I felt was inaccessible. As a visual artist my job is communication, and I’ve come to realise that combining figurative and abstract techniques lets me communicate information and emotion, using the unrecognisable human as a cipher, while leaving enough room for the viewer to find their own interpretation. This also gives me space to explore the technical aspects of making that I enjoy, like colour relationships, composition and scale.

GC: Looking at your works, I also wonder about their scale, how this ultimately impacts the viewer experience, how much of this is your intention, and the challenges that you face in terms of composition.

CH: My decisions about scale are 100% intentional. From a technical perspective, I enjoy the challenges of working on both a big and small scale. I experimented with making huge drawings (around 2x1.4m). The composition with big work took me a while to get to grips with; you have to nail it down. Working on a large scale is awe-inspiring, it’s impressive, but it’s hard to convey intimacy. I was interested in the expressive mark-making you can use with big work, and then combining that with more detailed intimate marks that mean you have to step in close and look with care. I’ve also done some really small work (5x6cm) and use surgical glasses to make these. Then you can make marks that aren’t visible with the naked eye, but they still have an impact on the image itself.

GC: In Mr Palomar by Italo Calvino, the protagonist (imagining himself as a bird) states that ‘it is only after you have come to know the surface of things that you venture to seek what is underneath’. It always strikes me how well you know the materials you use, how the surfaces react to your gestures or paint, hence the resonance with Palomar’s words. How important is it for you to have mastery over the materials? How much do you rely on chance in the process?

CH: It depends on the processes I use for each piece. Whilst I’m always experimenting with different surfaces, paints and mediums, with the Reasons paintings my material choices were calculated; I knew what effect I wanted and how to achieve it. I’m interested in how you can manipulate the qualities of particular materials in this way to influence meaning. In contrast, chance plays a large part in the Kiss monoprints because this medium is impossible to control in any meaningful way; you can try to get a similar result twice but it rarely happens! I like this. It can go to interesting places and it’s a complete antidote to being uptight about your work!

GC: Love and Rage. Where is one, where is the other?

CH: Tricky question. I’ve learned a lot about love in the last few years, and through this about myself. I’ve made a lot of friends. It might sound strange, but I never had many friends before, and I love it. The love in friendship is so important to me. I also fell in love for the first time, which taught me about allowing another person to grow, with love, and away from you if necessary, and the importance of loving yourself and maintaining boundaries. These are hard things! In the film Se7en, Morgan Freeman’s character says that ‘It’s easier to beat a child than it is to raise it. Hell, love costs. It takes effort and work’, and I agree. Whilst anger seems a more personal emotion, rage is easier for me to put a finger on. I am not an angry person. It is neglect, carelessness, unkindness, lack of thought and cruelty that make me enraged. My raging is against people suffering, the condition of humanity, the conflicts in the world at the moment, and the ceaseless disregard for the suffering of innocent people. That’s why the painting is called Blah blah blah – at the time of making, I was thinking how that seems to be the worldwide response to the conflict in Sudan. Similarly, Reasons to be Cheerful is a sarcastic dig. What have we got to be cheerful about, really? In spite of this though, I love people. I have great faith in their goodness and kindness. Ultimately, love touches me more deeply than rage. The Love Segments panels are more personal than some of the larger pieces in the show in the sense that they depict intimate experiences with the ones I love.

Gemma Cornetti is a freelance tutor at the City and Guilds of London Art School (Art Histories Department) and an Integrated Researcher (PhD) at CHAM, FCSH, NOVA University of Lisbon.